Benchmarking Retro Macs : Norton System Info

There are a number of classic Mac OS benchmarking tools available. Different ones have various benefits and personal preference is a major factor in choice. I’ve always used Norton’s System Info, which is provided as part of the Norton Utilities suite for Macintosh. I believe that it was first included with version 3 of Norton Utilities, but I need to verify that. As a kid, this was simply the only benchmark we owned, I like that it makes it clear what it is doing to benchmark (tests are named for the low level function that is being tested, often Macintosh Toolbox routines), and it uses a photo of two cats for the graphics tests that is clearly just a photo of a programmer’s pets. Its not even a very good photo, but this little human touch cheers me up every time I see it, and that’s worth a lot.

System Info requires System 7 to run, and so an alternative benchmarking tool such as Snooper would be needed if you are running System 6. The newest versions of Norton Utilities claim to need Mac OS 8.* but it isn’t actually true.

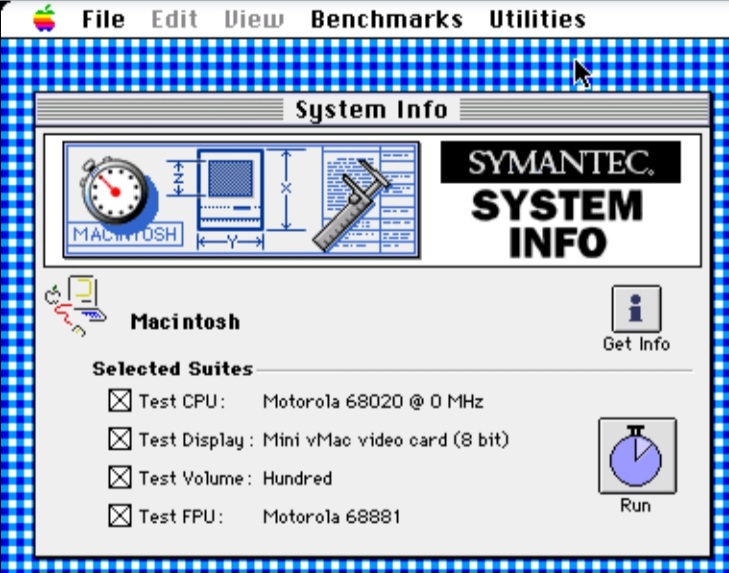

Over time, there were few obvious changes within the System Info application. Included benchmarks and System used as the baseline (100 in tests) varied through time. I… think it started as the SE, but haven’t seen this version lately… but more common versions were the Quadra 700, and later the Power Macintosh 6100/60. The following shows System Info’s default window on launch. Later versions show a splash screen while launching, earlier versions did not.

Features include

- Native 68k and PPC support.

- An extensive collection of included benchmark results files for both stock and some accelerated Macintosh computers.

- Top level CPU, 2D (Quickdraw) graphics, disk and FPU scores.

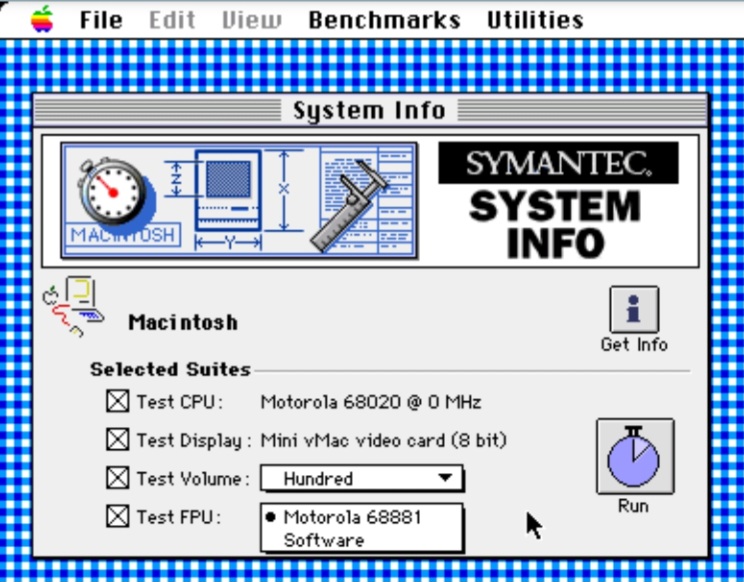

- Ability to select PPC or emulated 68020 performance on a PowerPC, and physical or software FPU where available.

- Ability to select which video card and which disk.

- Advanced mode which shows more detail during tests, and gives more detail in results. Graphical and tabulated results available, with the ability to show tabulated results in relative or absolute terms.

- Results can be easily shared as saved individual files for each test run.

- A detailed description of the computer and settings automatically saved with the results file.

- Warns about some system settings which may impact performance, such as AppleTalk, Virtual Memory, video bit depth and Disk Cache.

- A tiny application.

- Ability to export tab separated values (TSV).

Disadvantages

- New users don’t notice the need to enable advanced features and assume the tool is more simplistic than it is.

- As is often the case, the performance benefits of a relatively small cache are possibly exaggerated as the tests seem to be repetitive and fit within the cache (difficult because caches give significant real world advantages, but not in all instances).

- Tests are very much function based and not representative of real world activities.

- Graphics tests are only QuickDraw 2D, and don’t include any QuickTime, RAVE, QuickDraw 3D, Glide or OpenGL tests.

- Not scriptable?

- The CPU speed shown in the main window in MHz isn’t always correct, especially if the accelerator is only enabled during boot, or is able to change speed.

Tips and Tricks

- Even if the version of Norton you’re using is too new for the computer you are using, if you go into the “Norton Tools” folder and run “System Info” from there, it will launch in most circumstances, as long as you have System 7 or newer.

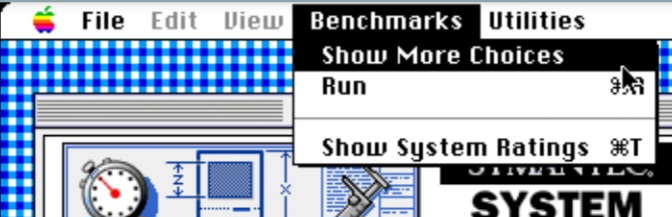

- To enable advanced options within the software, select “Show More Choices” from the “Benchmarks” menu. This provides a number of additional drop down menus for fine tuning and seeing results in a greater level of detail throughout the application, as well as some additional menu items.

- Note that generally, the higher the video bit depth you run, the slower graphics performance will be, except where acceleration is only provided at higher bit depths. It was fairly common for video cards to not provide acceleration at bit depths below 8bit, and a small number of cards only provided 24bit acceleration.

- Screen resolution doesn’t appear to have a significant impact on video scores for many machines, although running at 640×480 is probably best to ensure consistency with built in benchmarks. This said, Computers that use main memory as VRAM like the IIci, IIsi and 6100 can see significant CPU performance changes depending on video settings.

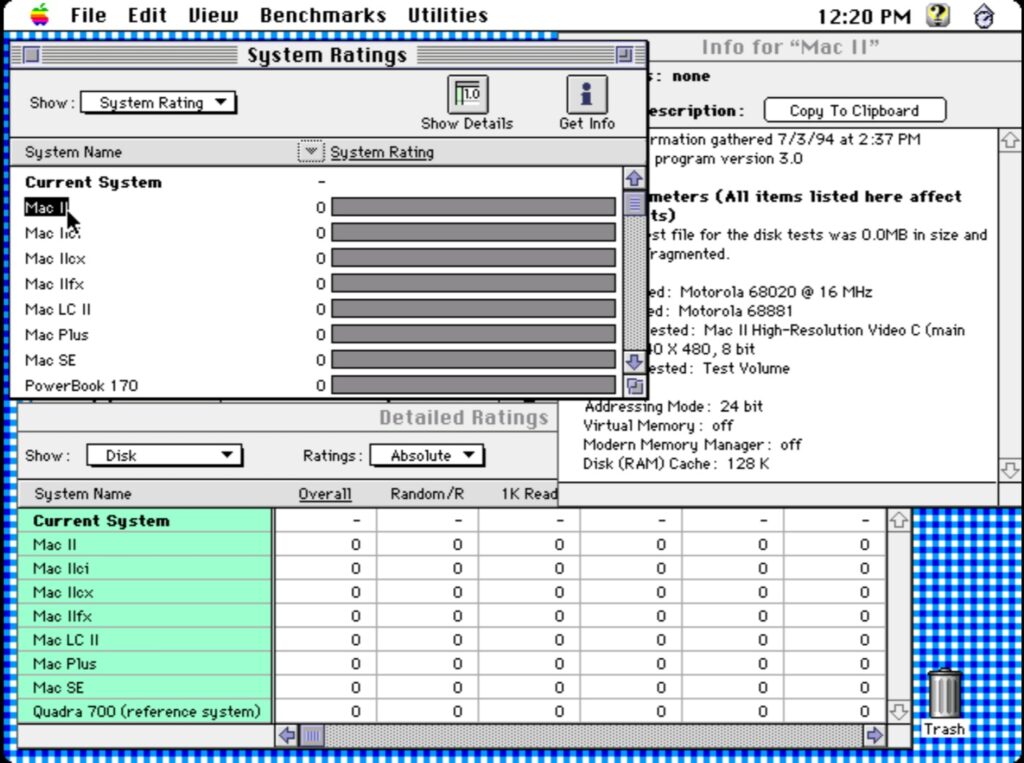

- When in the “System Ratings” window, selecting a system from the list and clicking the “Get Info” button (see image “All Results Windows” below) will show a description of the system the benchmark was performed on. Details are given of both hardware, software and some system settings.

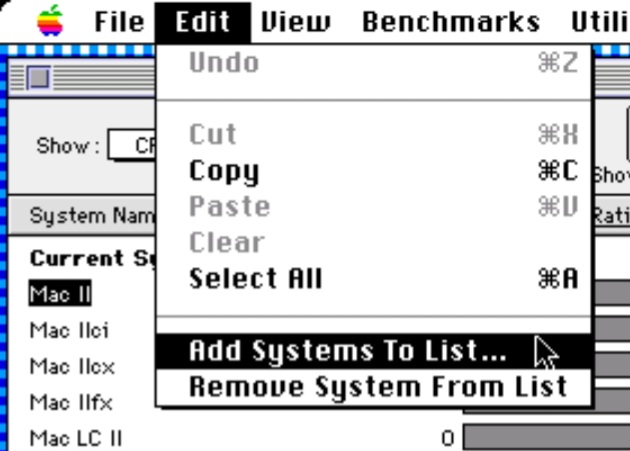

- Additional results supplied, but not shown by default, can be added to the various results windows using the “Add Systems To List” menu item from the “Edit” menu.

Running a Test

Use the “Selected Suites” checkboxes to enable and disable each of the CPU, video, disk and FPU test suites and if in advanced mode, select between the real and emulated CPU, video card, disk (in reality, the list given is mounted partitions) and FPU or software. Not all of these options will be available at all times, depending on the computer under test.

Link to video showing System Info benchmarks (at 3:22)

Once the options are as desired, click the “Run” button. Note that at this point Norton will inform you of any System settings it has detected which will impact the scores and which it thinks you should change. Unless you’re doing specific testing, such as comparing 24bit mode between video cards, it is generally advisable to follow this guidance. A restart may be required for some changes (for example, disk cache, and AppleTalk on some System versions).

After this the tests will start. Depending on the performance of your computer, they may take quite a few minutes to run, especially the disk tests. In the advanced mode, you will be given greater detail of what test is currently being undertaken and what each test scores. This can help with the boredom of waiting for the tests to complete.

Once the benchmarks have completed, System Info automatically opens the System Ratings window, and lists the tests just undertaken as “Current System”. It is probably a good idea to save the results at this point if you plan to keep them for comparison.

Reviewing Results

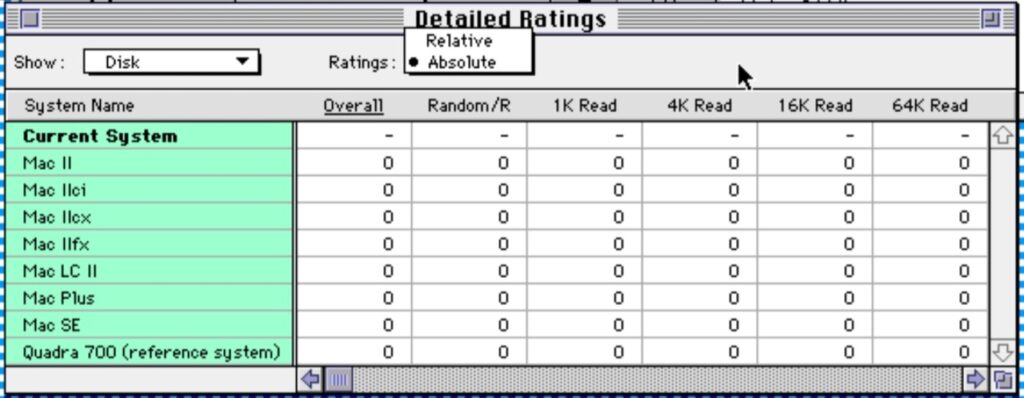

Note – the screenshot above incorrectly shows zeros for all results. This is an oddity of running the software within some emulators. Something I did for convenience when getting screenshots. On real hardware you will see actual scores for your and other computers.

Viewing Overall Rating / Test Category / Individual Tests

At the top left of the “System Ratings” window, there is a pop-up menu labelled “Show”. This allows you to select each of the four test categories, CPU, Video, Disk or FPU, as well as the default overall summary “System Rating”. The numbers to the right of each system name represent a score, relative to the baseline system (e.g. scaled where a Quadra 700 equals 100, or a 6100/60 equals 100 etc. dependant on the version of System Info you are using. The baseline system is identified in the list by the text “(reference system)” following its name). The bars to the right of these numbers (ordinarily) vary in length and graphically represent the score for each system.

If all tests were not run, the Current System will show as a dash “-” for the tests which were not completed, as well as for the overall “System Rating”.

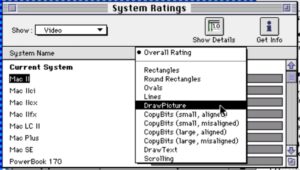

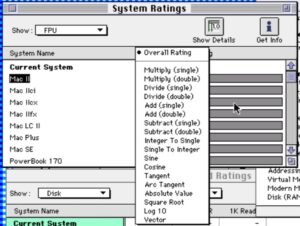

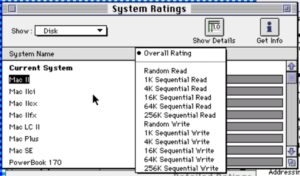

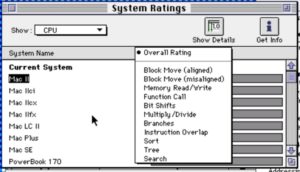

If advanced mode (i.e. with “show more choices” enabled), an additional drop down menu is available by clicking the downwards pointing triangle to the left of the “System Rating” column heading. This menu allows you to select individual tests for the category currently selected, for example, if you have selected “Disk”, then you will be able to choose to display specifically the random write, or perhaps 1K read test.

It is worth studying the results at this level, especially with respects to video accelerator performance, because it can be interesting to see how different cards perform in different areas. A card that scores well overall might be weak when it comes to rendering text compared to another card that scores lower overall. In this case, if your primary use case is… rendering text – the supposedly “slower” card might be the best card for you as it performs better in your application that mainly renders text.

Video Individual Test Results Menu

FPU Individual Test Results Menu

Disk Individual Test Results Menu

CPU Individual Test Results Menu

To assist in comparing results on a test by test basis, clicking the “Show Details” button presents tabulated results. Within this window, a drop down menu enables you to select between “Absolute” and “Relative” results. I find that generally, “Relative” is more usable with the exception of disk scores, as the “Absolute” scores for the disk results are given in KB/s, which is meaningful.

If you manually select a subset of results in the “System Ratings” window before clicking “Show Details” only details for those, plus the baseline system, will be shown.

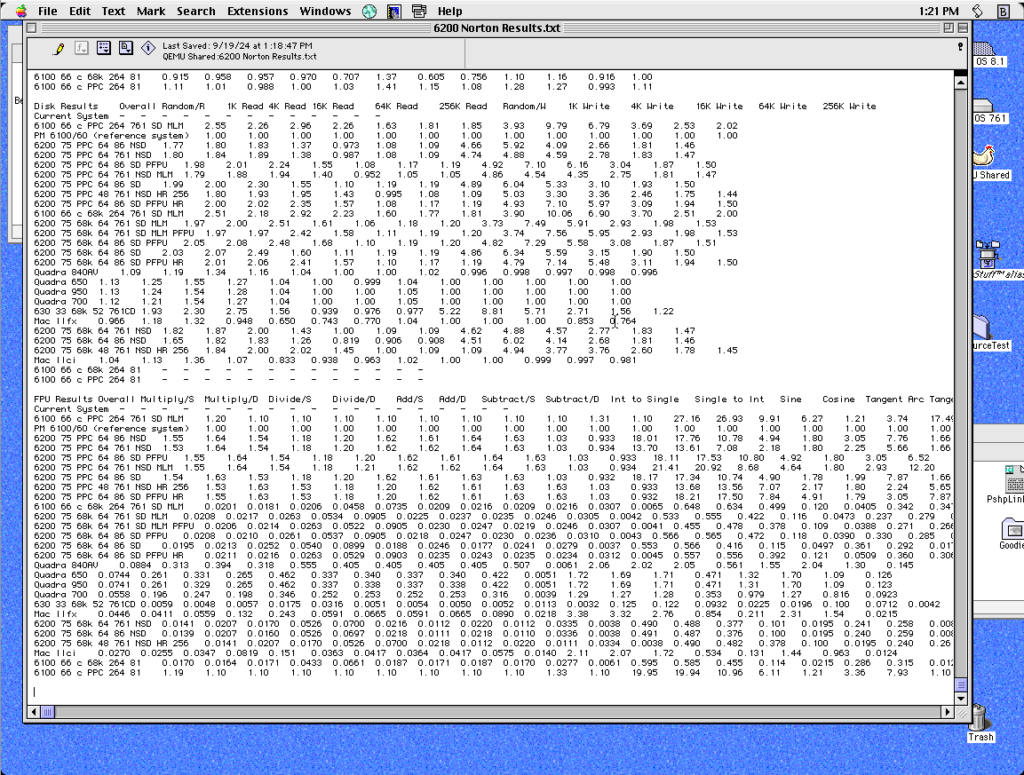

Exporting Results

While in the Detailed Ratings view, pressing Command-C will copy a summary of all results to the clipboard. This text can then be pasted into another application, such as for example, in the following screenshot, a text document. To remove unwanted entries either select a subset of results in the “System Ratings” window before clicking the “Detailed Ratings” button, or alternatively quit System Info and move unwanted benchmark files in the “Benchmark results” folder into the “Hidden Results” folder. Any results in the hidden folder wont show in the results lists / export. Moving them back afterwards will make them re-appear next time you relaunch the program.

Note that the exported text includes all result types (CPU, Video, Disk and FPU), not just the results that were currently being viewed. The data is Tab Separated Values (TSV) and should be fairly trivial to paste into a Spreadsheet such as Excel or ClarisWorks.

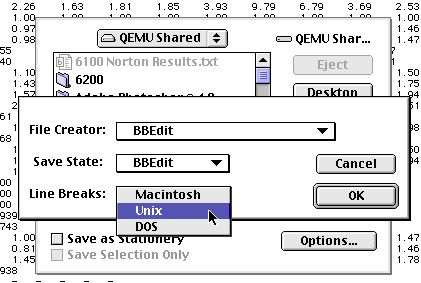

Moving data to a modern computer can be easily achieved with BBEdit. I recommend BBEdit, because it will run on 68k Macs, and is aware of the three common line ending types. By pasting in the data, selecting save, and then clicking the “Options…” button, you will get the following dialogue box, where you can select your preferred line ending type. I’m picking “Unix”, which is best for Linux and modern versions of Mac OS, but if you are on Windows, you will likely want to pick “DOS”.

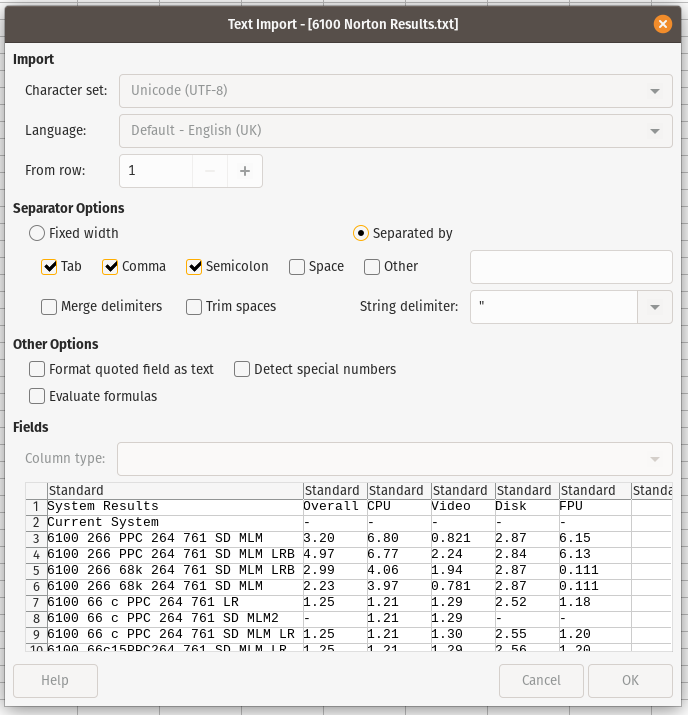

Name the file, including a “.txt” or “.tsv” file extension and save. Once you have moved the file to your modern computer, you should be able to trivially import the data. You may have minor issues if there are unusual characters, due to the classic Mac OS Roman text encoding. The following shows my example exported collection being opened in LibreOffice Calc.

Note – You should probably uncheck “Comma” and “Semicolon” if you have used these characters in your system descriptions, or if you are using continental European number formats.

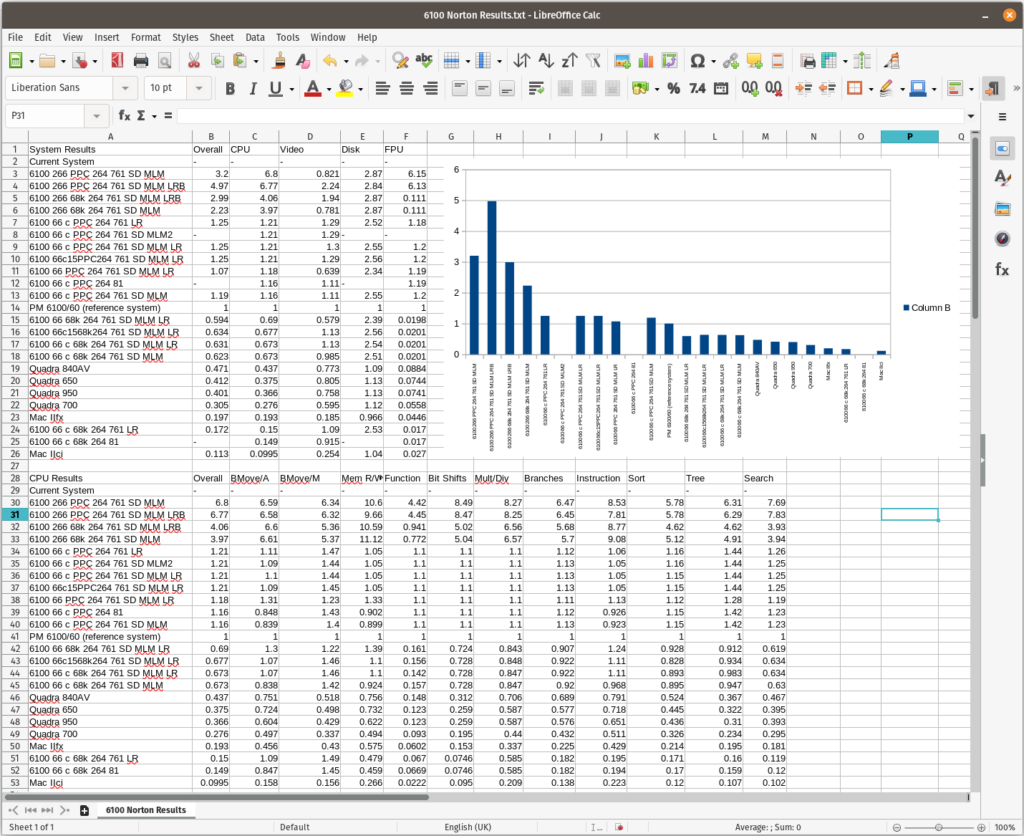

The following screenshot shows the text file imported with no further manipulation, other than creating a chart based on the “Current System” and “Overall” columns of the first table of data.

Description of the Individual Benchmark Tests

The following is an extract from the Norton Utilities 3.2 manual.

Manual Extract for Norton System Info Benchmarks

Variations in test results of up to 1 percent are normal. For disk tests, variations of up to 7 percent are normal due to disk drive operation.

CPU Benchmarks

Some CPU tests actually test more than the CPU itself. For example, some tests access memory (RAM), which tests not only the CPU, but the system bus, memory speed, and caching (if any). These factors can influence test results substantially. For the purposes of benchmarking, these factors are all considered to be part of the CPU.

BlockMove Aligned and BlockMove Misaligned: Measures the rate at which the Macintosh can move memory using the ROM trap BlockMove. On all Macintosh computers, BlockMove is highly optimized and thus is a good measure of memory bandwidth (how much data can be moved per unit time). An aligned and misaligned case are used because on some Macintosh computers performance is much poorer when data is not aligned properly. Newer models, such as the Power Macintosh computers, have excellent performance in both cases.

Memory Read and Write: This is also a memory bandwidth test, but the benchmark accesses memory in the way a program normally would and does not make use of any special machine instructions.

Function Call: Measures the overhead associated with making a series of function calls with arguments. Most application programs make large numbers of function calls.

Bit Shifts: Measures how fast bits can be shifted in a machine word. This type of instruction is used frequently by a wide variety of software.

Multiply and Divide: Measures speed of integer multiplication and division. The tests are slanted more towards multiplication. Application programs frequently use this type of instruction to access arrays.

Branches: Measures how fast code containing conditional branches can run. Branches are on of the most common types of instructions used and can substantially affect performance on some CPUs. Power Macintosh computers have a special processing unit dedicated to processing branch instructions.

Instruction Overlap: Measures the ability of the CPU to execute integer (not floating point) instructions at the same time it accesses memory. The benchmark is written in such a way that memory access should be able to execute at the same time all intervening computations are performed.

Sort: A high-level benchmark that sorts a large array using a quick-sort and insertion-sort hybrid algorithm that makes heavy demands on memory and looping constructs.

Tree: A high-level benchmark that builds a large, sorted binary tree by repeated insertion. Good caching and/or memory bandwidth can speed up this test considerably.

Search: A high-level benchmark that performs a sophisticated string-searching algorithm that makes extremely heavy demands on memory in a partially-sequential way. This test is designed to access memory in a way that most machines cannot cache effectively without a substantial amount of cache memory.

Video Benchmarks

The Video benchmarks test the speed at which common Quickdraw operations can be performed. The benchmarks are designed to measure frequently used operations – not esoteric transfer modes or rarely utilized Quickdraw routines. For example, scrolling operations are emphasized in the overall video rating because they are heavily used by all users. Note that as the video bit depth is reduced, video performance generally increases. If you compare video performance on two different systems, make sure to test at the same video bit depth.

Rectangles, Round Rectangles, and Ovals: These tests cycle through painting, erasing, filling, framing, and inverting the respective shapes with different fill patterns and colors, where appropriate.

Lines: Draws lines of varying slopes and colors. The video circuitry of some Macintosh computers is highly optimized for drawing lines.

Picture: Draws a bitmapped picture at the same bit depth of the screen. It tests the ability of Quickdraw to decode a PICT format picture and place its bits on the screen.

CopyBits: Measures how fast bits can be moved around on the screen using the CopyBits ROM routine, which is heavily used in screen drawing. The small cases are 32 by 32 (the size of a large icon). The small cases are significantly impacted by the overhead of calling Quickdraw and its setup. The large cases minimize this overhead and, thus, more accurately test the actual speed at which bits can be moved. Aligned (to a 32 pixel boundary) and misaligned cases test optimal and non-optimal situations.

DrawText: Measures how fast a sentence can be drawn on the screen. Primary emphasis is placed on drawing plain text, although bold and italic text are tested as well.

Scrolling: Measures how fast bits can be scrolled on the screen. Emphasis is placed on vertical scrolling, but some horizontal scrolling is also performed. Results of this test vary widely depending on the bit depth of the screen.

Disk Benchmarks

By design, the disk tests do not isolate disk speed alone. The benchmarks include factors applications normally experience, such as CPU speed, SCSI bus speed, impact of the disk cache, and fragmentation.

Random Read and Random Write: These benchmarks read or write data into a file in three 1MB bands. The data size read and written varies from 4 bytes to 4 kilobytes. These tests reflect seek time, the effects of the disk cache, and how fast a drive can process numerous small requests to read or write data. They are a good indicator of overall disk performance.

Sequential Read and Sequential Write (1K, 4K, 16K, 64K, and 256K): Measure how fast the drive can read/write data when requested in a specific size chunk. Some drives can transfer data efficiently only in large chunks, others are efficient with many small chunks, but slow down with large chunks. These sequential tests intentionally bypass the built-in disk cache (to eliminate cache overhead) and provide a better indicator of performance of the disk itself. Smart, disk-intensive applications such as Norton DiskDoubler Pro bypass the disk cache, when appropriate, to provide maximum performance. Few current applications employ this technique, however.

FPU Benchmarks

All FPU tests are directly comparable among themselves. For example, you can directly compare the speed of a multiply to an addition, square root, or cosine.

A single-precision floating-point number is 32 bits. Because of differences in the floating point formats supported on various machines, a double-precision number varies in size. For double precision, the fastest format available that is at least 64 bits in size is used.

Multiply, Divide, Add, and Subtract: Measure basic FPU performance in both single and double precision. On some machines, double precision may actually be faster than single precision because single precision numbers must first be converted to double precision before the calculation occurs.

Integer To Single and Single To Integer: Convert an integer number to a single precision floating point number and vice versa. Some machines have hardware instructions for both operations, some have neither, and some have just one. This accounts for dramatically different results that you may encounter, depending on which way the conversion goes.

Sine, Cosine, Tangent, and Arc Tangent: Measure trigonometric performance on double-precision numbers. These results can vary dramatically from computer to computer. Some older models of the Macintosh can actually outperform the new Power Macintoshes on these functions because the Power Macintoshes implement these routines in software.

Absolute Value, Square Root, and Log 10: Measure the absolute value, square root, and logarithm in base 10, respectively, of a double-precision number.

Vector: Measures how fast an array of numbers (vector) can be manipulated. Each element in the array is multiplied by a constant, a constant is added, and the result is stored back into the array (X’ = aX + B).

Getting Norton System Info

Norton System Info was provided as part of the Norton Utilities for Macintosh suite of software. The best way to get a copy of this is by buying a genuine copy on eBay, although I’m quite sure there are copies on Macintosh Garden.

Feedback on this Post

If you have any additional information which you wish to suggest is added to this page, or would like to correct any errors / inaccuracies, please use my contact form to let me know.